VULGATÆ EDITIONIS

BIBLIORUM SACRORUM

CONCORDANTIÆ

AD RECOGNITIONEM

JUSSU SIXTI PONTIF. MAX.

BIBLIIS ADHIBITA

RECENSITÆ ATQUE EMENDATÆ AC PLUSQUAM VIGINTI QUINQUE MILLIBUS VERSICULIS AUCTÆ INSUPER ET NOTIS HISTORICIS, GEOGRAPHICIS, CHRONOLOGICIS LOCUPLETATÆ

CURA ET STUDIO

F. P. DUTRIPON

THEOLOGI ET PROFESSORIS

EDITIO SECUNDA

BARRI-DUCIS

MDCCCLXVIII

Categoria: Libri

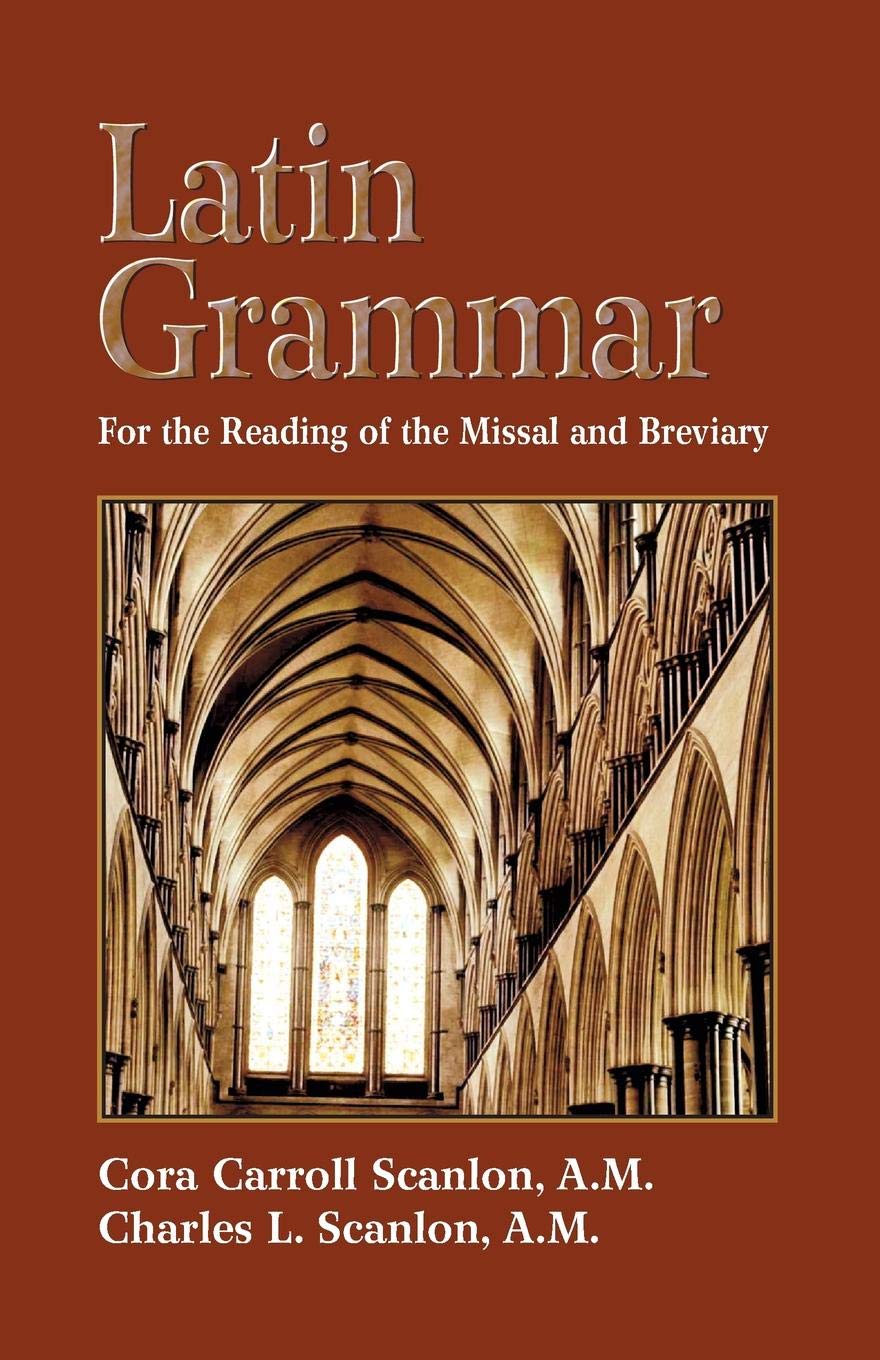

Latin Grammar for the Reading of the Missal and Breviary

By Cora Carroll Scanlon, A.M., Charles L. Scanlon, A.M.

This Latin grammar is intended for students who are entering seminaries or religious novitiates without previous study of Latin, for sisters in communities that recite the breviary, and for the growing number of lay people who use the Roman missal and the Roman breviary. Its twenty lessons, divided into fifty units, cover all the grammatical essentials for the intelligent reading of these two books. The vocabulary comprises the 914 words that make up the Ordinary of the Mass and the three Requiem Masses with their additional Collects, since these are the words that a daily user of the missal will encounter most frequently. However, to make the work as valuable as possible for those who use the missal in its entirety, as well as for those who wish to undertake the daily reading of the breviary, the Latin-English vocabulary at the end of the book includes not only all the words of the Roman missal, but also the complete vocabulary of the Roman breviary.

Teología de la Perfección Cristiana

La gloria de Dios como fin último absoluto, nuestra santificación como fin próximo al que hay que tender incesantemente, la incorporación a Cristo como único camino posible para conseguir ambas cosas: he ahí la quintaesencia misma de la vida cristiana.

Antonio Royo Marín, Teología de la Perfección Cristiana, p. 63.

Voltar-se para o Senhor e olhar para o Oriente

Enquanto o sacerdote se coloca na frente do altar, ele não reza em direção a uma parede, mas conjuntamente reza com todos em direção ao Senhor, tanto mais porque o que importava até agora não era formar uma comunidade, mas render culto a Deus por intermédio do sacerdote, representante dos participantes e unido a eles.

Por isto, falando da direção da oração, Santo Agostinho, bispo de Hipona, escreve: “Quando nos levantamos para orar, voltamo-nos para o Oriente (ad orientem convertimur) de onde o céu se levanta. Não que Deus só se encontre ali, ou que tenha abandonado as outras regiões da terra… mas para exortar o espírito a se voltar para uma natureza superior, ou seja, a Deus”.

Isto explica porque os fiéis, depois do sermão, se levantavam de seus assentos para a oração, que seguia, e se voltavam para o oriente. Santo Agostinho os convidada para isso freqüentemente ao terminar seus sermões, utilizando, à maneira de frase já consagrada, as palavras: “Conversi ad Dominum” (voltados para o Senhor!).

Aqui se pode evocar uma palavra de São Paulo. Consciente de que “todo o tempo que passamos no corpo é um exílio longe do Senhor. Andamos na fé e não na visão”, ele deseja estar ausente “deste corpo para ir habitar junto do Senhor” (ad Dominum) (2Cor 5,6-8).

Assim, pois, voltar-se para o Senhor e olhar para o Oriente, para a Igreja primitiva era uma única e mesma coisa.

Monsenhor Klaus Gamber, Voltados para o Senhor!

Traduzido por Luís Augusto Rodrigues Domingues

Giovannino Guareschi e il latino

Il latino è una lingua precisa, essenziale. Verrà abbandonata non perché inadeguata alle nuove esigenze del progresso, ma perché gli uomini nuovi non saranno più adeguati ad essa. Quando inizierà l’era dei demagoghi, dei ciarlatani, una lingua come quella latina non potrà più servire e qualsiasi cafone potrà impunemente tenere un discorso pubblico e parlare in modo tale da non essere cacciato a calci giù dalla tribuna. E il segreto consisterà nel fatto che egli, sfruttando un frasario approssimativo, elusivo e di gradevole effetto “sonoro” potrà parlare per un’ora senza dire niente. Cosa impossibile col latino.

(Giovannino Guareschi, Chi sogna nuovi gerani?)

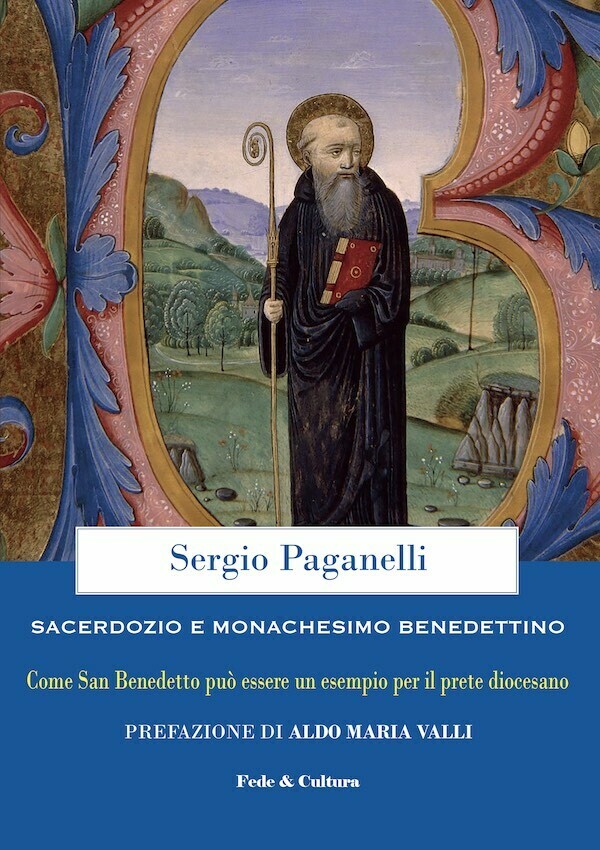

Sacerdozio e monachesimo benedettino

Del nostro amico e collaboratore don Sergio Paganelli, parroco di Sombreno (BG):

“Nell’attuale sbandamento e disorientamento dottrinale e pastorale, la spiritualità monastica benedettina è un esempio che può tornare a dare sostanza al ministero sacerdotale, specie nel caso del prete diocesano che vive immerso nel mondo, in un contesto difficile. L’autore di questo libro, in una lettera a un immaginario sacerdote novello, spiega come tornare a vivere l’essenziale con lo sguardo rivolto al cielo e a Dio pur nella complessa quotidianità di questo secolo”.

Disponibile qui e in libreria dal 31 ottobre 2019.

Leggi la prefazione al libro, di Aldo Maria Valli.

The Gregorian Missal

All the world knows that Americans are peculiar people when it comes to language. If it is not in English or if an English translation isn’t nearby, we tend to treat the text as if it belongs to someone on another planet. Foreign tongues boggle our minds, and rather than get busy and actually learn another language (never!) we just toss it aside.

It’s my own private theory that this tendency has long hindered the dissemination of the church’s music in the United States. The Graduale Romanum, the official songbook of the Roman Rite, is entirely in Latin.

Hand it to a typical musician and it will not penetrate their brains. It’s not the Latin in the music so much as the absence of English. Call it ignorance or bigotry if you want but it is a fact of reality. Latin chant will never go anywhere in this country until singers can feel a sense of ownership over the meaning, and that means translations.

This is why the CMAA produced The Parish Book of Chant as the new book for people. It opens up the Latin chant tradition to all English speakers.

The complementary book for the scholas — the book containing the propers of the Mass — is the Gregorian Missal published by the Solesmes Abbey in France. This book is a treasure, a glorious thing to behold. The running headers are all in English. All Latin texts are translated. And this allows the great revelation to unfold: here is the music of the Mass.

(from Sing like a Catholic by Jeffrey A. Tucker, p. 180)

The Musical Shape of the Liturgy

The reforms of the liturgy resulting from the Second Vatican Council have greatly increased the freedom of choice of liturgical music; the council also encouraged the composition of new music for the sacred liturgy. However, every freedom entails a corresponding responsibility; and it does not seem that, in the years since the council, the responsibility for the choice of sacred music has been exercised with equal wisdom in all circles. To judge by what is normally heard in the churches, one might even conclude that the Church no longer holds any standards in the realm of sacred music, and that, in fact, anything goes.

The council did not leave all up in the air, however, and if its Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy had been seriously heeded, a living tradition would still be alive everywhere, and we would have added musical works of some permanence to the “store of treasures” of sacred music. The council laid down some rather specific norms which can serve as a basis for developing an understanding of sacred music and thus for choosing wisely.

In its chapter on sacred music, the council declared that the solemn sung form of the liturgy is the higher form, that of all the arts music represents the greatest store of traditional treasures of the liturgy, that music is the more holy insofar as it is intimately connected to the liturgical action, and that Gregorian chant is the normative music of the Roman rite. Moreover, in speaking of innovations in general, it required that new forms derive organically from existing ones.

From Sacred Music 102, no. 3 (1975), reprinted in The Musical Shape of the Liturgy by William Peter Mahrt (2012)

Archives of Sacred Music Journal

Archives of the journal Sacred Music from 1965 to last year are listed here, and most are available for download in PDF format.

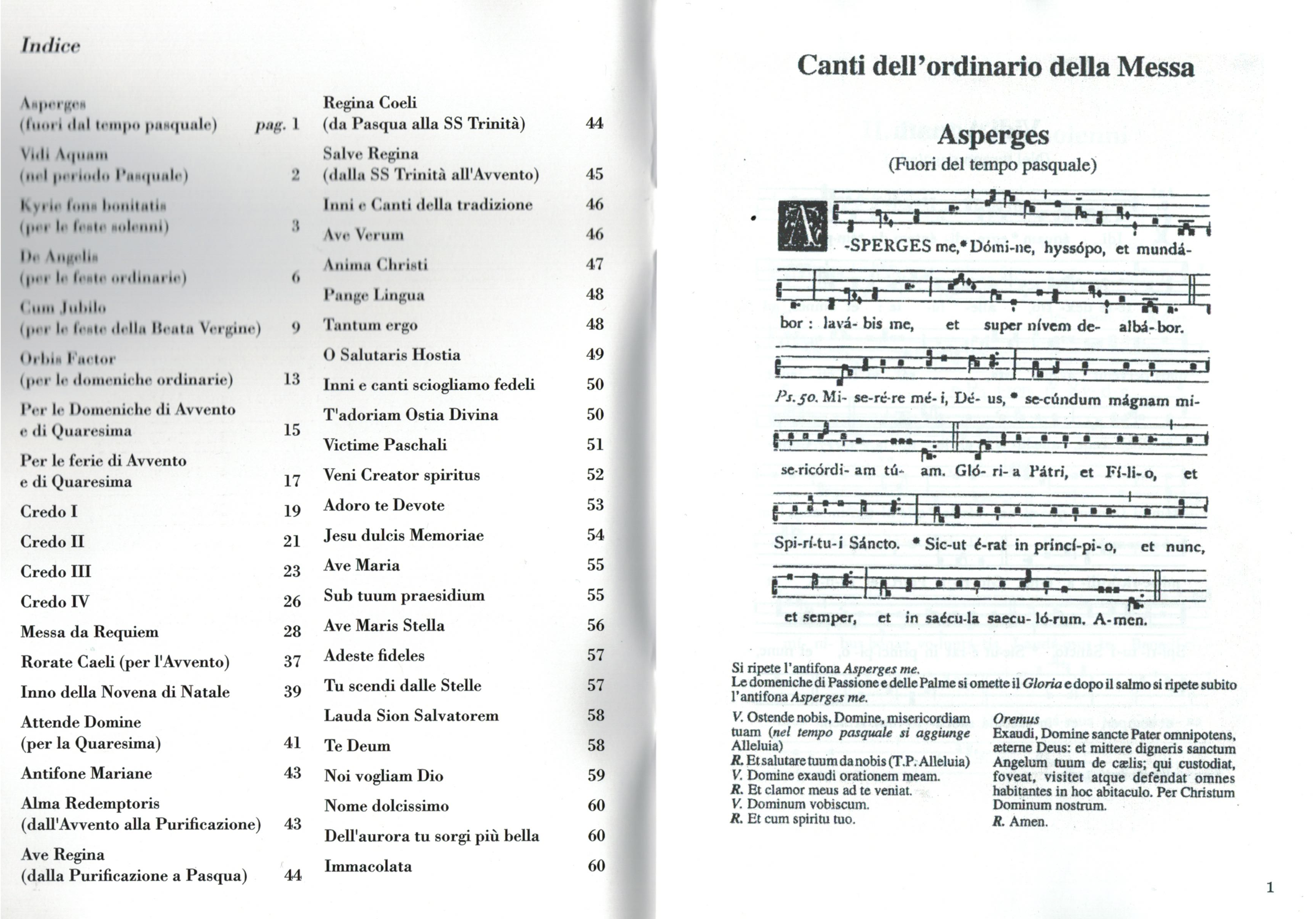

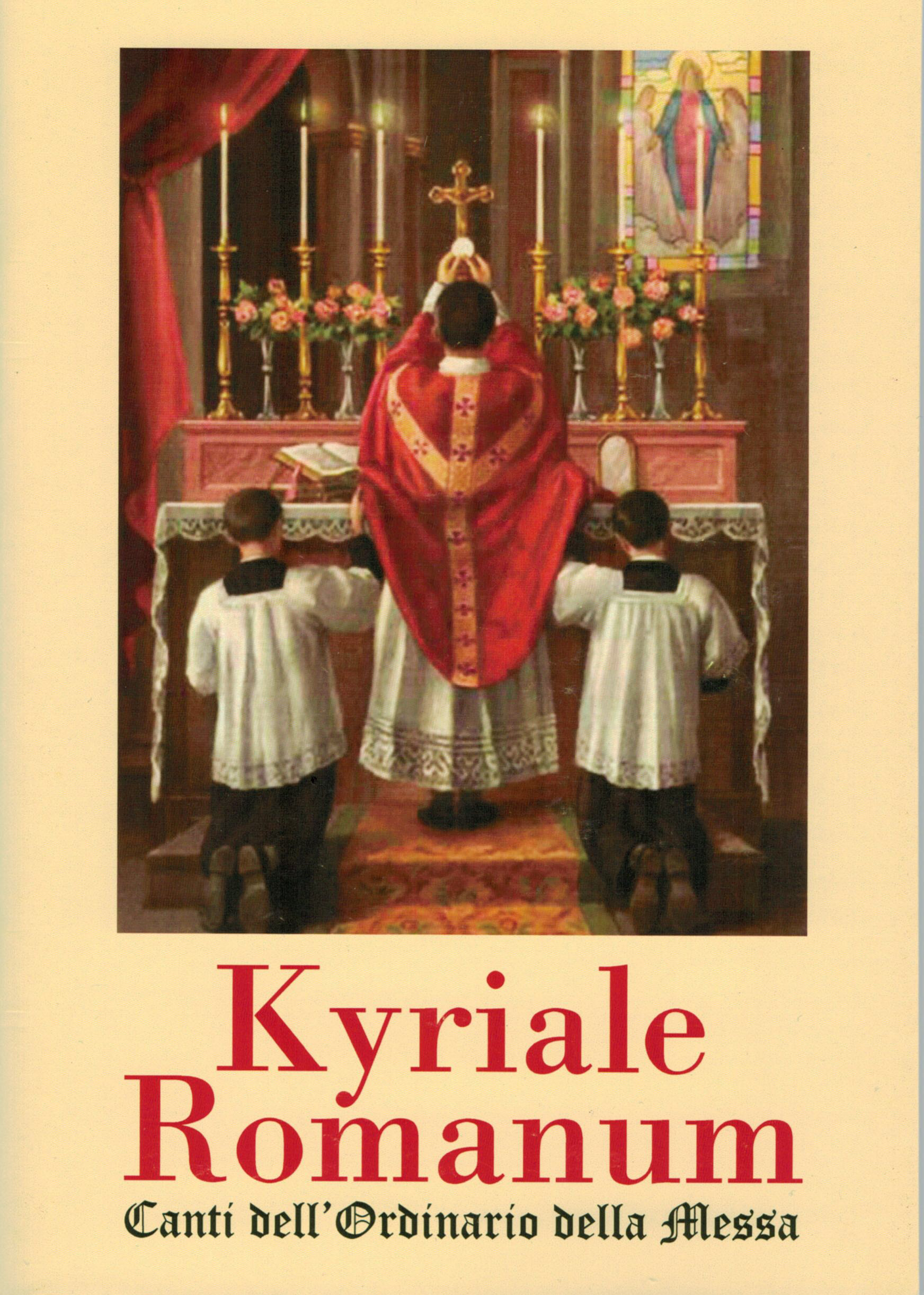

Kyriale Romanum – Canti dell’Ordinario della Messa

Nuova edizione a cura della Chiesa della Madonna della Neve di Bergamo. Per informazioni sulla disponibilità e sull’acquisto: newsletter@madonnadellanevebergamo.it