Articolo di mons. Marco Agostini apparso su L’Osservatore Romano del 20 agosto 2010:

È impressionante la cura che l’architettura antica e moderna, fino alla metà del Novecento, riservò ai pavimenti delle chiese. Non solo mosaici e affreschi per le pareti, ma pittura in pietra, intarsi, tappeti marmorei anche per i pavimenti.

Mi sovviene il ricordo del variopinto tessellatum delle basiliche di San Zenone o dell’ipogeo di Santa Maria in Stelle a Verona, o di quello vasto e raffinato delle basiliche di Teodoro ad Aquileia, di Santa Maria a Grado, di San Marco a Venezia, o quello misterioso della cattedrale di Otranto. L’opus tessulare cosmatesco luccicante d’oro delle basiliche romane di Santa Maria Maggiore, San Giovanni in Laterano, San Clemente, San Lorenzo al Verano, di Santa Maria in Aracoeli, in Cosmedin, in Trastevere, o del complesso episcopale di Tuscania o della Cappella Sistina in Vaticano.

E ancora gli intarsi marmorei di Santo Stefano Rotondo, San Giorgio al Velabro, Santa Costanza, Sant’Agnese a Roma e della basilica di San Marco a Venezia, del battistero di San Giovanni e della chiesa di San Miniato al Monte a Firenze, o l’impareggiabile opus sectile del duomo di Siena, o le pelte marmoree bianche, nere e rosse in Sant’Anastasia a Verona o i pavimenti della cappella grande del vescovo Giberti o delle settecentesche cappelle della Madonna del Popolo e del Sacramento, sempre nel duomo veronese, e, soprattutto, lo stupefacente e prezioso tappeto lapideo della basilica vaticana di San Pietro.

In verità la cura per l’impiantito non è solo cristiana: sono emozionanti i pavimenti a mosaico delle ville greche di Olinto o di Pella in Macedonia, o dell’imperiale villa romana del Casale a Piazza Armerina in Sicilia, o quelli delle ville di Ostia o della casa del Fauno a Pompei o la preziosità delle scene del Nilo del santuario della Fortuna Primigenia a Palestrina. Ma anche i pavimenti in opus sectile della curia senatoria nel Foro romano, i lacerti provenienti dalla basilica di Giunio Basso, sempre a Roma, o gli intarsi marmorei della domus di Amore e Psiche a Ostia.

La cura greca e romana per il pavimento non era evidente nei templi, ma nelle ville, nelle terme e negli altri ambienti pubblici dove la famiglia o la società civile si radunava. Anche il mosaico di Palestrina non era in un ambiente di culto in senso stretto. La cella del tempio pagano era abitata solo dalla statua del dio e il culto avveniva all’esterno innanzi al tempio, attorno all’ara sacrificale. Per tale ragione gli interni non erano quasi mai decorati.

Il culto cristiano è, invece, un culto interiore. Istituito nella stanza bella del cenacolo, ornata di tappeti al piano superiore di una casa di amici, e propagatosi inizialmente nell’intimo del focolare domestico, nella domus ecclesiae, quando il culto cristiano assunse dimensione pubblica trasformò la casa in chiesa. La basilica di San Martino ai Monti sorge sopra una domus ecclesiae, e non è la sola. Le chiese non furono mai il luogo di un simulacro, ma la casa di Dio tra gli uomini, il tabernacolo della reale presenza di Cristo nel santissimo sacramento, la casa comune della famiglia cristiana. Anche il più umile dei cristiani, il più povero, come membro del corpo mistico di Cristo che è la Chiesa, in chiesa era a casa e signore: calpestava pavimenti preziosi, godeva dei mosaici e degli affreschi delle pareti, dei dipinti sugli altari, odorava il profumo dell’incenso, sentiva la gioia della musica e del canto, vedeva lo splendore degli ornamenti indossati a gloria di Dio, gustava il dono ineffabile dell’eucaristia che gli veniva amministrata in calici d’oro, si muoveva processionalmente sentendosi parte dell’ordine che è anima del mondo.

I pavimenti delle chiese, lontani dall’essere ostentazione di lusso, oltre a costituire il piano di calpestio avevano anche altre funzioni. Sicuramente non erano fatti per essere coperti dai banchi, questi ultimi introdotti in età relativamente recente allorquando si pensò di disporre le navate delle chiese all’ascolto comodo di lunghi sermoni. I pavimenti delle chiese dovevano essere ben visibili: conservano nelle figurazioni, negli intrecci geometrici, nella simbologia dei colori la mistagogia cristiana, le direzioni processionali della liturgia. Sono un monumento al fondamento, alle radici.

Questi pavimenti sono principalmente per coloro che la liturgia la vivono e in essa si muovono, sono per coloro che si inginocchiano innanzi all’epifania di Cristo. L’inginocchiarsi è la risposta all’epifania donata per grazia a una singola persona. Colui che è colpito dal bagliore della visione si prostra a terra e da lì vede più di tutti quelli che gli sono rimasti attorno in piedi. Costoro, adorando, o riconoscendosi peccatori, vedono riflessi nelle pietre preziose, nelle tessere d’oro di cui talvolta sono composti i pavimenti antichi, la luce del mistero che rifulge dall’altare e la grandezza della misericordia divina.

Pensare che quei pavimenti così belli sono fatti per le ginocchia dei fedeli è commovente: un tappeto di pietra perenne per la preghiera cristiana, per l’umiltà; un tappeto per ricchi e poveri indistintamente, un tappeto per farisei e pubblicani, ma che soprattutto questi ultimi sanno apprezzare.

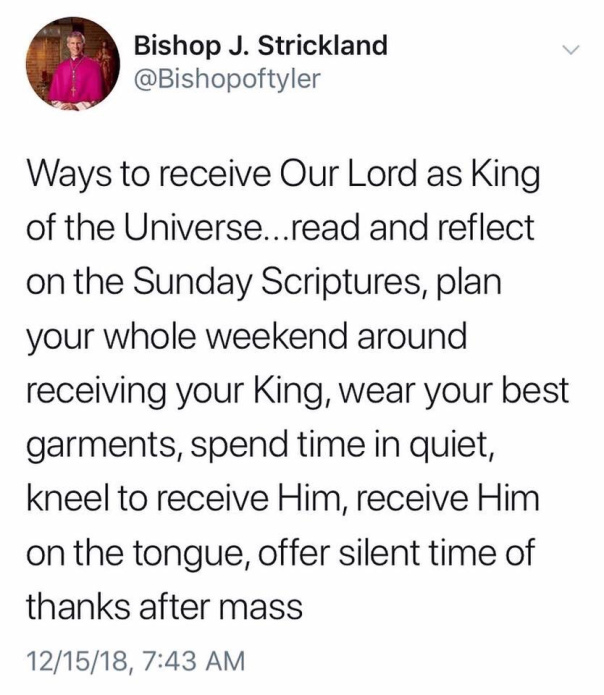

Oggi gli inginocchiatoi sono scomparsi da molte chiese e si tende a rimuovere le balaustre alle quali ci si poteva accostare alla comunione in ginocchio. Eppure nel Nuovo Testamento il gesto dell’inginocchiarsi si presenta ogni qualvolta a un uomo appare la divinità di Cristo: si pensi ai Magi, al cieco nato, all’unzione di Betania, alla Maddalena nel giardino il mattino di Pasqua.

Gesù stesso disse a Satana, che gli voleva imporre una genuflessione sbagliata, che solo a Dio si devono piegare le ginocchia. Satana sollecita ancora oggi a scegliere tra Dio o il potere, Dio o la ricchezza, e tenta ancora più in profondità. Ma così non si renderà gloria a Dio per nulla; le ginocchia si piegheranno a coloro che il potere l’hanno favorito, a coloro ai quali si è legato il cuore attraverso un atto.

Buon esercizio di allenamento per vincere l’idolatria nella vita è tornare a inginocchiarsi nella messa, peraltro uno dei modi di actuosa participatio di cui parla l’ultimo Concilio. La pratica è utile anche per accorgersi della bellezza dei pavimenti (almeno di quelli antichi) delle nostre chiese. Davanti ad alcuni verrebbe da togliersi le scarpe come fece Mosè davanti a Dio che gli parlava dal roveto ardente.